External heating systems

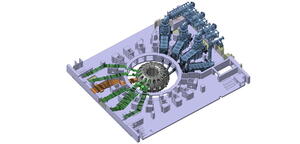

ITER’s heating and current drive systems: electron cyclotron resonance heating (green), ion cyclotron resonance heating (orange), and neutral beam injection (blue).

The temperatures inside the ITER Tokamak must reach 150 million °C, or ten times the temperature at the core of the Sun. The hot plasma must then be sustained at these extreme temperatures in a controlled way.

Plasma heating begins inside the machine with the magnetic fields that are used to control the plasma. Because the plasma is an electrical conductor, the magnetic fields use to initiate the plasma induce a high-intensity electrical current. As this current travels through the plasma, electrons and ions become energized and collide. Collisions create "resistance" that results in heat but, paradoxically, as the temperature of the plasma rises, this resistance—and therefore the heating effect—decreases. Heat transferred through high-intensity current, known as ohmic heating, is limited to a defined level (on the order of 10-15 million °C). In order to obtain still higher temperatures and reach the threshold where fusion can occur, external heating must be applied.

In ITER, several types of external heating will work concurrently. The new plans for ITER construction and operation that have been proposed to the ITER Council (the 2024 ITER baseline) impact the heating mix of ITER, most notably requiring an upgrade of the electron cyclotron resonance heating system as described below.

Neutral beam injection

Two heating neutral beam injectors on ITER will each contribute 16.5 MW of heating power to the plasma; space for a third has been reserved in the neutral beam cell of the Tokamak Building. (A smaller neutral beam—the diagnostic neutral beam—will probe the plasma to provide information on the helium ash density produced by the D-T fusion reactions in the fusion plasma.)

ITER’s heating neutral beam injectors will shoot uncharged high-energy particles into the plasma where, by way of chaotic motion and collision, they will transfer their energy to the charged plasma particles.

In the injector, a beam source generates electrically charged deuterium ions that are accelerated through a succession of grids to a kinetic energy of 1 Mega electron Volt (MeV). A "neutralizer" rips them of their electrical charges, allowing them to penetrate the tokamak's magnetic cage and, by way of multiple collisions with the particles inside the plasma, raise plasma temperature.

The large plasma volume at ITER has imposed new requirements on this proven method of injection: the particles will have to move three to four times faster than in previous systems in order to penetrate far enough into the plasma, and at these higher rates the positively charged ions become difficult to neutralize. At ITER, for the first time, a negatively charged ion source has been selected to circumvent this problem. Although the negative ions will be easier to neutralize, they will also be more challenging to create and to handle than positive ions. The additional electron that gives the ion its negative charge is only loosely bound, and consequently readily lost.

A test program is underway now at the ITER Neutral Beam Test Facility in Padua, Italy to investigate challenging physics and technology issues of neutral beam injection in advance of the installation of the heating neutral beam equipment at ITER. More on the ITER Neutral Beam Test Facility here.

One of the powerful neutral beam injectors that will send high-energy particles into the plasma.

High-frequency electromagnetic waves

ITER’s two wave-based heating systems are designed to deliver energy at frequencies that match the oscillations of particles inside the plasma—a matching called "resonance." The energy increases the velocity of the particles' chaotic motion, and at the same time their temperature.

Electron Cyclotron Resonance Heating (ECRH) heats the electrons in the plasma with a high-intensity beam of electromagnetic radiation at a frequency of 170 GHz, the resonant frequency of electrons; the electrons in turn transfer the absorbed energy to the ions by collision. In the new baseline, ITER will rely on the ECRH system to contribute 40 MW of heating power to the plasma during the initial phase of operation, SRO (Start of Research Operation) and up to 67 MW in later phases of operation. ECRH also has a role in initiating each plasma shot and in suppressing certain instabilities by depositing heat in very specific areas of the plasma. The electromagnetic waves are generated by powerful 1 MW gyrotrons that have a pulse duration of more than 500 s. To reach 67 MW with radiofrequency sources of the type planned, 80 sources (called gyrotrons) would be required to be connected by transmission lines to ECRH launchers near the plasma. Alternately, the possibility of installing higher power gyrotrons can also be investigated.

Ion Cyclotron Resonance Heating (ICRH) transfers energy to the ions in the plasma through a high-intensity beam of electromagnetic radiation with a frequency that can be chosen between 40 and 55 MHz. ICRH will deliver 20 MW of heating power (10 MW during initial operation and 20 MW in later phases) to the plasma through two radio frequency sources connected by transmission lines to plasma-heating antennas.

Burning plasma

Ohmic heating, neutral beam injection and high-frequency waves will work in conjunction on ITER to bring the plasma to a temperature where fusion can occur. Ultimately, researchers hope to achieve a "burning plasma"—a plasma in which the heat from the fusion reactions is confined within the plasma efficiently enough for the self-heating effect to dominate any other form of heating and external heating methods can be strongly reduced. A burning plasma in which at least 50 percent of the energy to drive the fusion reaction is generated internally is an essential step to reaching the goal of fusion power generation. As the first burning plasma device in the world, ITER will usher in a new era of fusion research.