T time for JET

26 Jun 2014

-

Nick Holloway, Culham Center for Fusion Energy

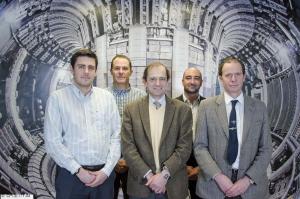

The project management team from left to right: Ben O'Meara (Project Lead Engineer), Robyn Davies (Technical Clerk), Tim Jones (Project Sponsor), Alex Rowley (Requirements/Systems Engineer) and Robert Warren (Project Manager).

Engineers at Culham Centre for Fusion Energy (CCFE) have begun to prepare Europe's flagship fusion experiment JET for a new set of full-power fusion experiments using tritium fuel.

The tests, currently scheduled for 2017-18, will be the first with tritium since 2003 and will act as an important "dress rehearsal" in preparation for ITER's operation with tritium.

To generate large amounts of power in commercial tokamak reactors, a combination of two heavy hydrogen nuclei—deuterium (D) and tritium (T)—will be required to fuel the fusion furnace. However, supplies of tritium are scarce and its radioactivity makes it impractical for use in most fusion research labs. For fusion power stations neither issue should be a problem; a lithium "blanket" around the tokamak will react with the fusion neutrons to produce tritium fuel within the device itself, and remote-controlled maintenance systems will ensure safe handling of material exposed to tritium and fusion neutrons. (JET has been at the forefront of the development and highly successful implementation of remote handling technology.)

Today though, to avoid the complications of tritium, the vast majority of fusion research is conducted with deuterium fuel only. This provides very accurate results that can be scaled up to predict the performance of future DT reactors. But for the best simulation of how ITER will operate with DT, there is nothing like the real thing—a series of fusion tests with both fuels.

That's where JET comes in. As the world's largest operating tokamak and the only such device capable of storing, using, recovering and recycling tritium, it has a unique role in fusion research. And upgrades since the 2003 tritium campaign—particularly the ITER-like inner wall of beryllium and tungsten—have effectively turned JET into a "mini-ITER"; as close as any present-day device can get to its operating conditions.

Another series of DT experiments on JET will therefore provide scientific information to help make ITER a success, as well as give physicists and engineers vital experience of running fusion machines with tritium.