3D cost containment

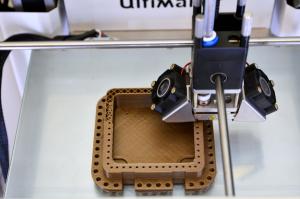

By providing designers with a concrete, three-dimensional experience of the object under development, mockups play an important part in the design and configuration process of the ITER installation's components. Up to now, mockups have been produced by specialized companies using ITER Organization 3D files that contain component specifications.

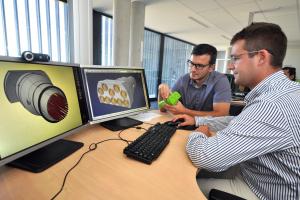

"In the mockup manufacturing process, the preparation of the 3D file represents the largest part of the work," explain Christophe Penot, designer, and Jérôme Ferréol of the Diagnostic Division support team.

Producing a plastic 3D mockup in-house doesn't cost a lot: a mockup of an ITER port plug (0.1 percent of its actual size) for instance costs about five euros in raw material and the hours the designer spends in finalizing the 3D file. The printing itself takes between one hour and a few days depending on the complexity of the component.