Inventions

Where have all the neutrons gone?

22 Jan 2018

-

Kirsten Haupt

It is not unusual in the course of a work day at the world's largest scientific experiment to rely on creativity to resolve the challenge at hand. But less common, is when an inventor's technique is rewarded for not only adding value to ITER, but also attracting the interest of outside firms. A case in point.

Michael Loughlin (left) was recognized by the ITER Director-General Bernard Bigot in early January for an innovation that not only adds value to ITER, but also attracts the interest of outside firms.

An expert in nuclear analysis and shielding at ITER, Michael Loughlin's job is to understand and model the behaviour of neutrons in order to shield both equipment and people from their impact.

In the course of his work he had the idea for a web-based application for radiation mapping that was then developed under contract by AMEC (now part of the Wood Group). ITER licensed this software to AMEC for commercial exploitation in 2013—the first time that ITER issued a license for intellectual property developed to address an ITER-specific issue.

On 8 January, Loughlin received recognition for his creativity and inventiveness from the ITER Director-General. "It is important to demonstrate that we deliver real innovation," said Bernard Bigot as he presented Loughlin with the award. "I hope to encourage others to follow this example."

So, what is this innovation about? Nuclear fusion creates radiation in the immediate environment of the fusion reactor through escaping neutrons and gamma rays. Materials and equipment need to be able to withstand that radiation and people need to be protected against its harmful effects.

In the conception of their systems, engineers need to know about the radiation conditions at any location within the Tokamak Building and two adjacent buildings, the Tritium and Diagnostics buildings. Extensive calculations have been carried out, Loughlin explains. "We predicted and modelled what the radiation is likely going to be." The modelling considered data on the geometry and structure of the buildings—including information on materials, thickness of walls and floors, openings, and pipes systems—and on how radiation would travel in these locations.

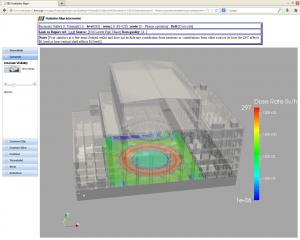

The software tool helps to visualize radiation conditions in any given location in the Tokamak Complex by producing 3D maps.

The result is an enormous database. Loughlin's initial idea led to the creation of a software tool that provides access to the database, helps query it, and then produces 3D radiation maps for any location within the buildings during the different operating phases of ITER. The user-friendly application is web-based and can be run on mobile devices.

Who might be interested in the software? There are a number of industries that could find this software application useful, such as the nuclear fission industry or medial facilities using radiation technology. "It's for anybody who wants to have a good overview over radiation conditions in a facility," says Loughlin.