Large fusion conference opens in Gandhi's hometown

As a nation of close to 1.4 billion inhabitants, heavily dependent on fossil fuels (81.4 percent) for electricity generation, India sees its future in nuclear energy in all its forms. "It is clearly an essential option for energy safety," said Rajagopala Chidambaram, a key architect of the country's nuclear program and the former Chair of India's Atomic Energy Commission. "I don't see any other option on the horizon."

For Nawal Prinja, another figure from India's nuclear sector who spoke on the first morning of the conference: "Fusion is our future. Fusion technology is already working; what's missing is the extraction of energy from fusion reactions."

Fifty years ago in Novosibirsk, at the third gathering of what was then called the Conference on Plasma Physics and Controlled Nuclear Fusion Research, a new type of fusion device, christened with the Russian acronym "tokamak," entered centre stage (see box below).

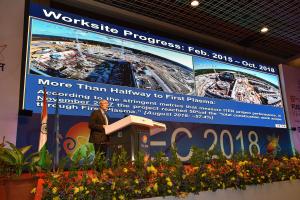

Today, the hopes of the worldwide fusion community rest on the largest tokamak ever built and the first designed to deliver a net energy production. ITER, whose progress toward First Plasma was presented by Director-General Bernard Bigot at the opening session of the conference, will be the focus, whether directly or not, of a large part of the presentations and posters.

With ITER now 58 percent of the way to First Plasma, a new era in fusion energy research has opened. It is against this background that, in Mahatma Gandhi's Ahmedabad-Gandhinagar, scientists and engineers from 40 countries will present and discuss the key physics and technology issues of fusion research ... for the benefit of all mankind.