Marvels of the subterranean world

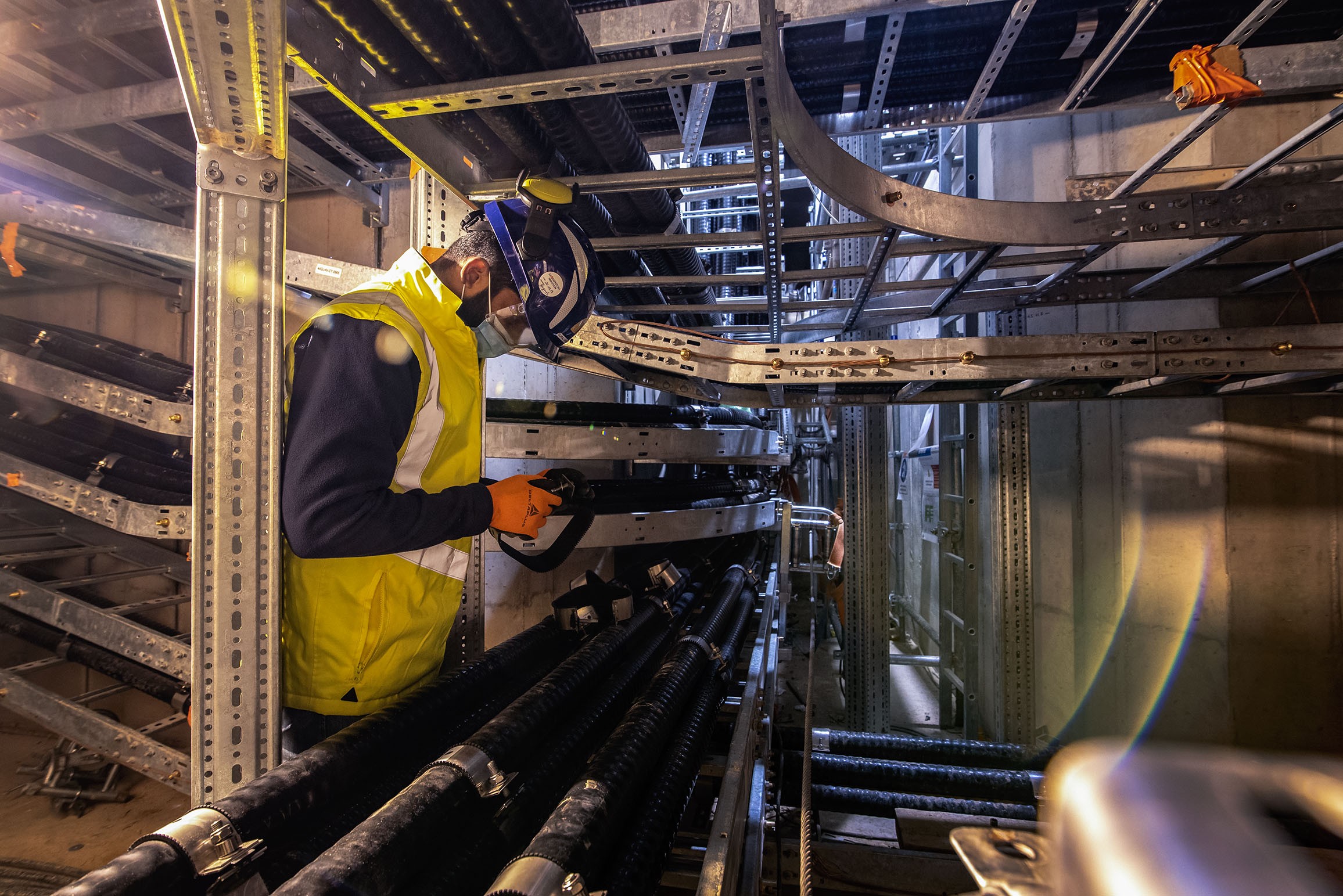

Each tray supports up to nine cables, each one as thick as an arm. In certain places, where the cables bend towards the surface, the impression is that of tentacles belonging to a creature lurking in the depths.

From the "cathedral," located below the west entrance of the magnet power conversion buildings, cables head in all directions, eventually reaching the four corners of the platform.

Since July 2020, workers have been busy installing the 66 kV cables that connect the converters in the electrical switchyard (where the 66 kV network originates) to the equipment inside the magnet power conversion buildings. Along this 150-metre distance, work is now 60 percent complete; it will be finalized in another six to seven months.

Procured by China, the cables are delivered in drums and unspooled by a powerful winch located at the opposite end of the gallery. All along the underground pathway, contractors from the Slovakian company Busbar 4F are monitoring the operation, guiding the cables along rollers and into their dedicated trays. The pulling force exerted by the winch is proportional to the length of cable already unspooled, reaching the equivalent of 50 to 60 workers at its strongest. Fifty drums, each carrying 4.7 tonnes of cable, have been unspooled so far.

Each cable carries a 600 Amp current and there are two cables per phase—which makes six cables per converter. With 26 hungry converters and a few auxiliaries to feed, the 66 kV network requires 216 individual cables, 150 of which have already been installed.

When the required 53 kilometres of 66 kV cables are installed, similar operations will be conducted for the 22 kV network, which is shorter (41 kilometres) and comprises "only" 114 cables of a slightly smaller diameter.

See the gallery below for more information.