A clear picture is emerging

Under a vast plastic tent set up in the Cryostat Workshop, workers in protective gear are busy cleaning the surface of a thermal shield panel that has been stripped of its cooling pipes, with the last traces of welds removed. A short distance away, in the Assembly Hall, other workers are assembling the platform used to support the 440-tonne vacuum vessel sectors during the preparation phase prior to their installation in vertical tooling. These two activities are the only visible evidence, so far, of the intense work performed over the past few months, and especially in the weeks preceding the end-of-year break, to define a repair strategy for the ITER tokamak's thermal shield panels and vacuum vessel sectors.

Two and a half years into its machine assembly phase, ITER is facing challenges common to every industrial venture involving first-of-a-kind components. "There is no scandal here," says ITER Director-General Pietro Barabaschi. "Such things happen. I've seen many issues of the kind, and much worse..."

The defects identified in two key components, the thermal shield panels and the vacuum vessel sectors, can and will be fixed. In-house and external experts have identified the causes and explored different repair options and strategies. Although details remain to be worked out with the contractors that will be chosen to execute the repairs, a clear picture is now emerging.

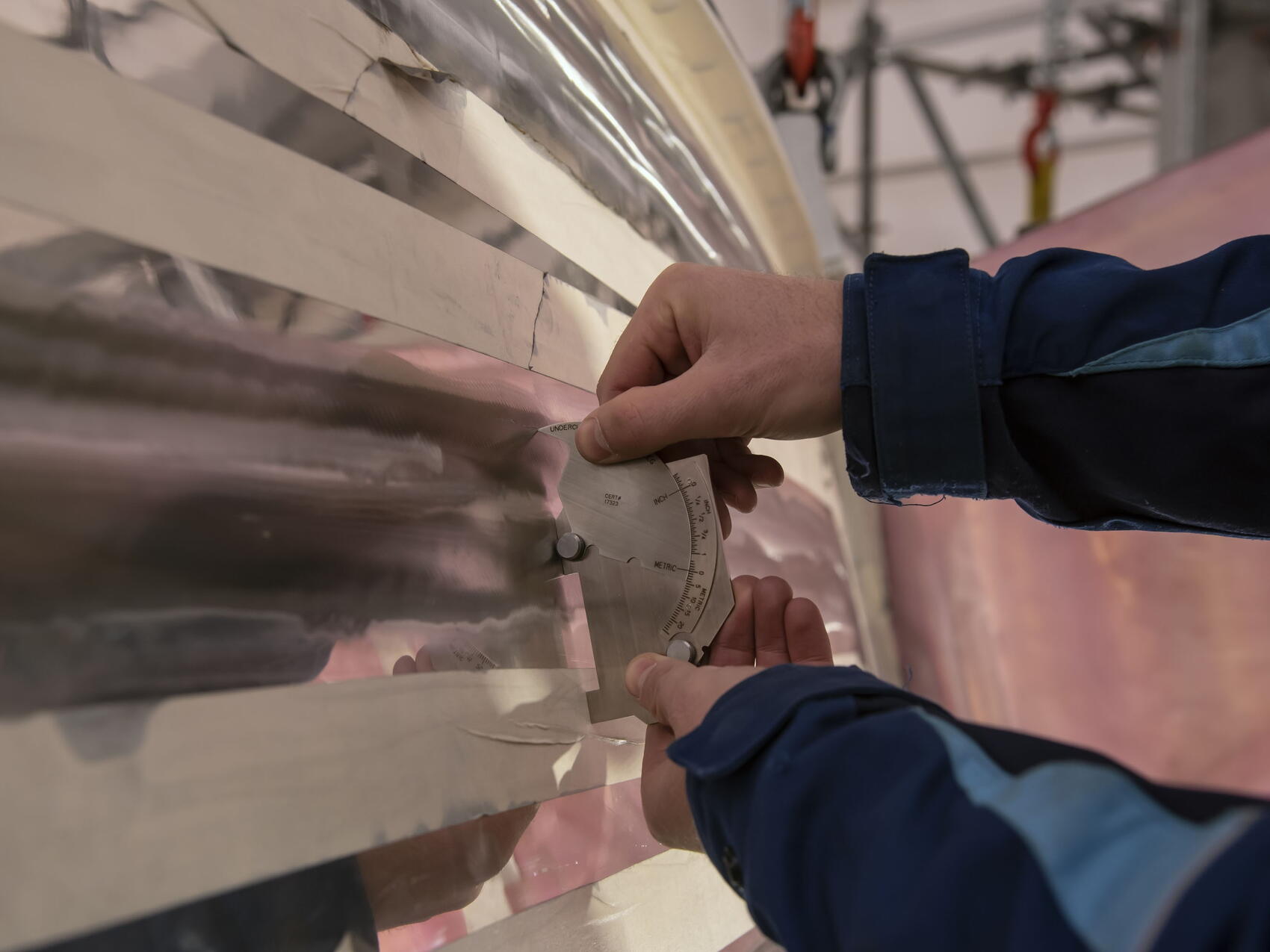

As reported in late November, the issue with the thermal shield panels is one of "stress corrosion cracking" that is affecting the cooling pipes welded to the component surface. In the course of the manufacturing process, chlorine residues were trapped in tiny pockets near the welds, causing cracks up to 2.2 millimetres deep. The problem was identified on three, yet-uninstalled vacuum vessel thermal shield panels. (There are two outboard panels and one inboard panel for each of the nine vacuum vessel sectors, or 27 panels in all.) "When you find three instances of cracks, it is a red alarm because there could be hundreds of locations where cracks could develop," says Barabaschi.

The decision was taken to remove and replace all cooling pipes (23 kilometres in total) from the panels and to choose a solution that would exclude the risk of stress corrosion cracking. But a question needed to be answered first: would the removal of the pipes alter the panels' dimensions, rigidity, or their capacity to accommodate a new set of piping? The ongoing activity under the big white tent inside the Cryostat Workshop is all about answering these questions.

As for the pipes themselves and their attachment process, different solutions have been explored. "We looked at quite a number of different options," explains ITER Tokamak Assembly Specialist Brian Macklin. "In pipe fabrication, we will use a different steel formulation—more resistant to corrosion. For joining the pipes to the panels we contemplated using clamps rather than welds, but concluded that welding was still best, provided we use a lower-energy process and slightly different welding wire."

Who will execute the repairs and where are still open questions. "We hope to launch the tender in the first week of February and have a contractor by the end of March, which is very fast by our standards," says Macklin. Discussions with the selected industrial partner will determine whether the components are repaired on site or in an outside facility.

There is also a strong possibility that "a few" panels will be re-manufactured. "This option might actually be cheaper than repairing them," says the ITER Director-General, "and in any case I prefer to have a few spares."

The ITER management is making the assumption that the crack issue in the cooling pipes could be systemic, affecting all thermal shield components—including the lower cryostat thermal shield, which has already been installed. Due to the difficulty of lifting the component back out of the crowded environment of the assembly pit, it has been decided to leave the original cooling network in place, disconnect it, and attach a new set of pipes to replace it.

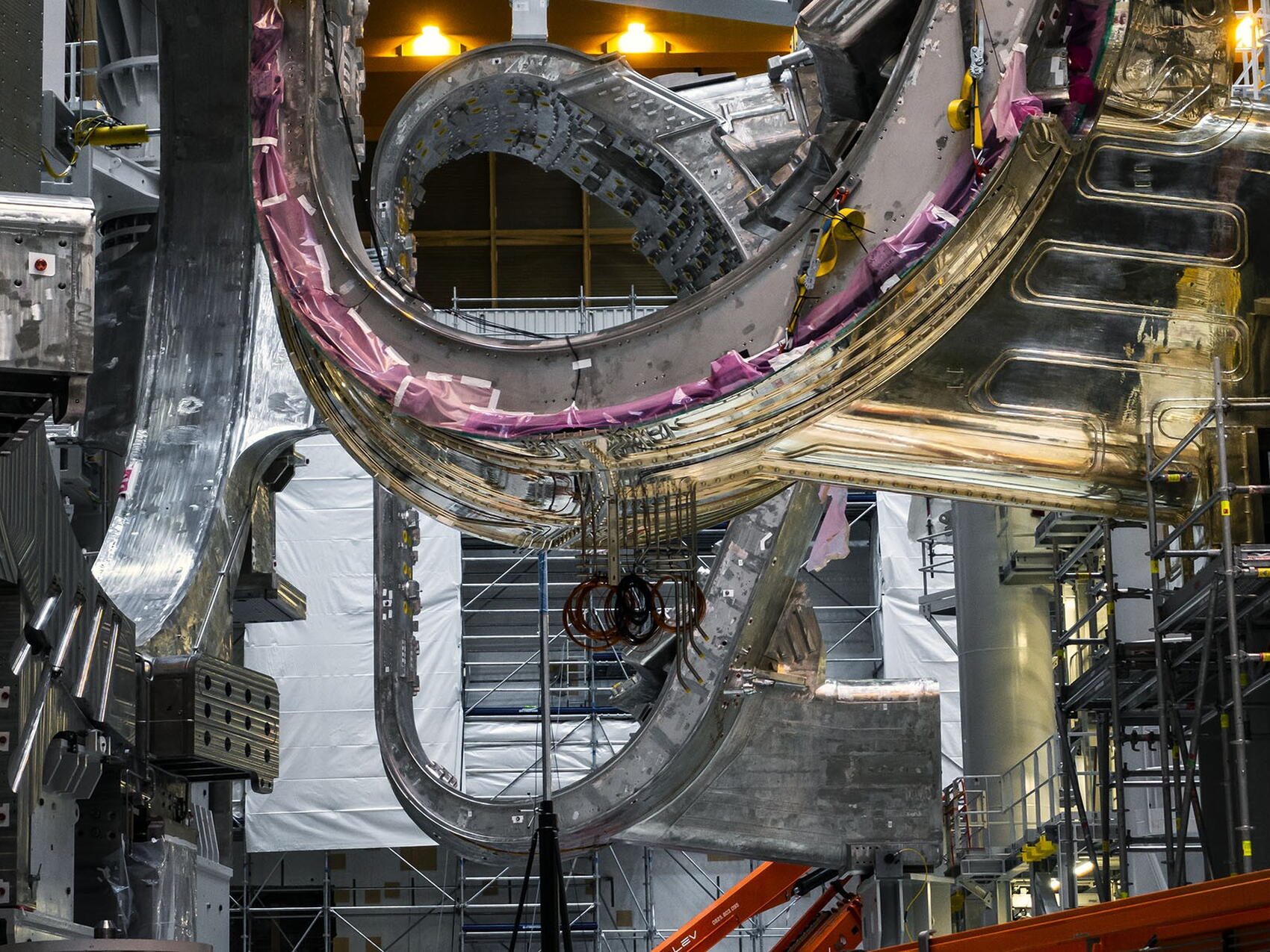

The other component issue that the ITER project is addressing relates to the dimensional non-conformities discovered in the three vacuum vessel sectors that have already been delivered. (One of these sectors forms the core of the "module" which is already in place in the assembly pit.)

Vacuum vessel sectors are among the most massive components of the machine, as high as a five-storey building and as heavy as an Airbus A380.

D-shaped vacuum vessel sectors are formed from four segments welded together. It is during this welding process that deviations from nominal dimensions occurred in different locations on the sectors' outer shells. These deviations were more important than the specified limit and modified the geometry of the field joints where the sectors are to be welded together in the tokamak pit, thus compromising the access and operation of the bespoke automated welding tools.

Schematically (very schematically...), valleys must be filled and hills must be shaved in order to restore the geometry to nominal and recover the ability to weld the sectors together. "Machining is best; depositing metal is a bit more risky," says Macklin. "We will need to combine both options, and we are tailoring the solution as best as we can. Repairs will only start once the build-up process has been fully qualified."

The quantity of filler material anticipated is not insignificant: approximately 73 kilos for sector #6 (the one already installed in the assembly pit), 100 kilos for sector #1(7) and 400 kilos for sector #8, the most affected of the three.

Considering the importance of the vacuum vessel as the ITER installation's first nuclear safety barrier, an approved notified body, acting on behalf on the French nuclear regulator ASN (Autorité de sûreté nucléaire), is closely involved in the technical discussions on repair options. The weld deposition process is currently being qualified, and the deposited material will be subject to 100 percent non-destructive examination by either radiography or ultrasonic testing.

"We are pursuing a very aggressive schedule to perform molten metal deposition tests on 'coupons' provided by the manufacturer, to carry out welding simulations at our industrial partner ENSA, and of course to select contractors in order to have everything ready to go in June."

Repairing the three steel behemoths will require complex logistics: sector #8, presently installed in one of the sector sub-assembly tools, will be lifted out and placed in a horizontal position on the platform currently being assembled at the opposite end of the Hall, then moved to another building where repairs will be executed. The operation, scheduled for April, will require a reverse use of the upending tool so that it can "down-end" the 440-tonne component.

Sector #1(7) will remain where it is in tooling, and be stripped of its thermal shield panels to prepare for repairs. Sector #6 will take the place of sector #8 on tooling after the module it belongs to is lifted out of the Tokamak pit—an operation planned in late May or early June. Sector #6 will have to be disassembled from its toroidal field coils and thermal shield panels, so that the vacuum vessel sector is ready for repair in late 2023.

The duration and cost of the repairs cannot, at this stage, be precisely estimated. "A substantial amount of time is required, and time always costs money," says Director-General Barabaschi. "But we can take advantage of the present situation to reorganize and increase the experimental content of the operational phase and reach full-power operation—our real and final objective—with minimum delay."