How ITER quantifies fusion power

To prove fusion’s promise, ITER must not only create energy—it must also measure it with great precision.

ITER plans to routinely demonstrate a fusion gain of Q=10, meaning that for 50 MW of injected heating power across the plasma, 500 MW of fusion output will be produced. This can only be done if there is a way of accurately measuring the output—and that job is entrusted to neutron diagnostics. “I work on systems that measure neutrons, which are a product of the fusion reaction,” says Silvia di Sarra, diagnostics engineer at ITER. “They tell us how much power is being produced inside the machine.”

But the detectors that record neutron flux in the ITER tokamak have to be calibrated first to ensure measurement accuracy—an activity that takes place inside of the vessel using small neutron generators. “Neutron generators are compact accelerators that use fusion reactions to produce neutrons with well-known properties,” explains di Sarra. “By comparing our detectors’ readings to this known reference, we can establish a precise measurement scale. It’s similar to how you would adjust a bathroom scale by putting something of known weight on it and correcting the reading.”

Typically, in other tokamaks, neutron sources are placed inside the machine in all the positions occupied by the plasma. But this approach won’t be enough at ITER because the generators have limited power and the vacuum vessel is large and full of heavy shielding. “At ITER, we will only be able to place the neutron sources near the detectors in a relatively small number of places,” says di Sarra.

Another consideration at ITER is machine utilization. Since activities have to be put on hold during calibration, the calibration process needs to be as efficient as possible.

A hybrid approach to precision

“Extensive pre-studies are underway to optimize source placement and minimize machine downtime,” says di Sarra. “For areas we can’t reach, we will use detailed computer simulations to extrapolate the detector response.”

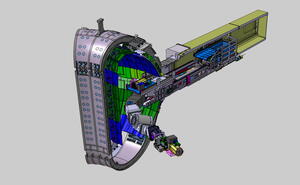

This hybrid approach—combining direct measurement and modelling—will compensate for the limited reach of the neutron sources. “One big advantage is that we have extremely detailed CAD data,” she says. “From that, we can generate very accurate neutronic models of the entire machine—down to the smallest bolts.”

These models allow the team to predict neutron transport and detector responses throughout the reactor. “They help us plan the calibration, estimate what the detectors should measure at each source position, and later correct the results during operation. When we can’t measure directly, we simulate.”

The modelling itself is done using powerful Monte Carlo particle-transport codes: MCNP, an older tool that is validated for use by nuclear installations in France, and OpenMC, a newer, Python-based code that’s much faster and more flexible, with clear visualizations. “The codes complement each other,” says di Sarra. “We cross-check the results of the two—running one classical simulation and one with the modern tool—to ensure consistency.”

Calibration of the ITER neutron diagnostics is positioned in a narrow time gap between two construction phases in 5 or 6 years. “Assembly activities will have concluded, but the integrated commissioning will not yet have begun,” says di Sarra. “It’s the ideal window to carry out calibration.”

Trust and teamwork at the core

Di Sarra sees similarities between one of her favorite hobbies, climbing, and the long-term nature of her work at ITER. “In climbing, before you start, you check your partner’s knot and belay device,” she says. “At ITER, it’s the same. We work in teams, follow strict procedures, and rely on each other completely.”

That trust is essential in an environment where setbacks are inevitable. “There have been moments when components had to be removed and reinstalled,” she says. “You have to trust your colleagues are doing their best, just as they trust you. We all focus on our part of the work and help each other when needed.”

“Whether it’s in climbing or in fusion, you always check twice,” says di Sarra. “You keep calm, and you keep going—one careful step at a time.”