60 years ago: the speech that changed everything

They sailed on a warship. Some say that they wanted to show their military might; others that they felt too old—although they were both barely over 60—or too embarrassed to arrive for a state visit in an outdated two-engine Ilyushin propeller plane¹.

Whatever the reason, the arrival in Portsmouth, UK, of a Soviet cruiser (escorted by two destroyers) carrying Nikolai Bulganin, President of the Council of Ministers of the USSR, and Nikita Khrushchev, Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party, caused a sensation. The date was 18 April 1956 and this was the first-ever visit of Soviet leaders to the West.

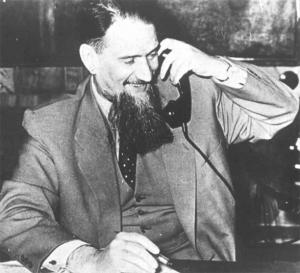

Igor Kurchatov (1903-1960) had been running the Soviet nuclear program since 1943. Now that the USSR was on an equal strategic footing with the US, "The Beard," as he was known to his colleagues at the Laboratory of Measuring Apparatus of Academy of Science (in fact, the Institute for Atomic Research) could now focus his remarkable energy on another quest, maybe the most promising but also the most difficult of all: "the thermonuclear synthesis problem" —in other words, the harnessing of thermonuclear energy for peaceful uses.

It is hard to imagine, from a distance of 60 years, the impact and echo of Igor Kurchatov's conference at the Atomic Energy Research Establishment in Harwell, Oxfordshire — the Holy of Holies of Britain's nuclear research.

It took time to convince politicians that, at that stage, collaboration in the field of fusion was about fundamental science and didn't pose any threat of strategic or military nature.

Only in September 1958, in Geneva where the United Nations held its Second International Conference on the Peaceful Uses of Atomic Energy, did the seeds that were sowed in Harwell begin to sprout.