Making sure ITER is ready for operation

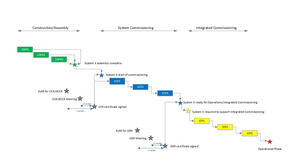

As the project advances toward the construction and operational objectives defined in Baseline 2024, integrated commissioning has become increasingly central to ensuring ITER’s success.

Instead of progressing as originally planned toward a modest first-plasma demonstration at low current, ITER is now preparing for a more robust start to scientific exploitation, with hydrogen and deuterium plasmas and pulses up to 15 MA during the first research phase. “We are going to do many more things than we had originally planned,” says Isabel Nunes, Commissioning & Operations Responsible Officer. “Before, we were just demonstrating breakdown. Now we are actually performing the first objectives of our Research Plan.”

ITER’s Start of Research Operation (SRO) phase will require all of the essential systems needed for sustained pulses—a blanket, inertially cooled first-wall panels, the divertor, and magnets performing at full magnetic energy. “Starting with normal plasma operation, and not just a limited demonstration, means that our work has expanded dramatically,” says Nunes.

What has not changed is the definition of integrated commissioning, which is the systematic process of testing, verification, and fine-tuning of interconnected plant systems to ensure they are ready for operation.

The first round: for Start of Research Operation

The objectives for ITER’s first integrated commissioning phase include demonstrating that ITER can achieve the vacuum conditions required for plasma operation, cooling and energizing the superconducting magnets to full performance, and integrating the control, safety, fuelling, and heating systems required for the first campaigns.

The work begins with pump-down and leak testing of the vacuum vessel and cryostat, followed by a carefully controlled cooldown of the superconducting magnets to 4.5 K—a slow, cautious process. “This will be the first time* we cool down the superconducting coils, so we have to go slowly,” Nunes explains. “As we energize the coils, the forces can be huge—they can damage a coil if we’re not careful.”

From there, teams take on many of the tasks that were once distributed across several later phases. Wall conditioning is one of the largest. “We expect to spend two months preparing the inner wall of the vacuum vessel for operation,” says Nunes. “You have to remove water, oxygen, hydrogen, hydrocarbons—everything that would cool the plasma and prevent breakdown.”

Diagnostics and magnetic systems add another layer of complexity, requiring parallel activity during magnet energization. “When you energize the coils, you are also calibrating the magnetic diagnostics, and at the same time checking the cooling because the temperature rises,” Nunes explains. “Everything must be coordinated.”

Under the new plan, all of these tasks must be performed in approximately 18 months—a much more ambitious set of activities for first-phase commissioning (IC-I) than in the previous baseline.

The second round: for the first deuterium-tritium phase

After the Start of Research Operation phase, expected to last 27 months, major new hardware will be installed—and that means another round of commissioning.

ITER’s permanent first wall, and the installation of neutral beam injectors, additional heating and four test blanket modules (TBMs) will require system-level testing first, followed by full integration into the rest of the plant. The objectives of second-phase integrated commissioning (IC-II) are to integrate the tritium fuel cycle, commission the test blanket modules and their lithium-lead and helium-cooled loops, condition the neutral beam injectors up to 870 kV with hydrogen, and complete the safety and interlock systems required for burning-plasma operation.

IC-II also includes recommissioning all the systems validated in the first integrated commissioning and operation phase. Diagnostics must be re-aligned and recalibrated, additional heating gyrotrons and beamlines must be integrated, and shielding performance must be assessed using radioactive sources to benchmark radiation transport models for the next operational phase, DT-1 (Deuterium-Tritium 1). The license to introduce tritium depends on these activities being completed successfully.

Every time the vacuum vessel is vented, we need a restart phase, says Nunes. “You have to cool down again, energize the coils, bake the vessel, condition the walls, and remove impurities.” The same logic applies to software and control systems: “Every time we restart, we recommission if a system has changed or been upgraded but also if no changes were made, because we must demonstrate that the software and hardware still work as expected.”

This disciplined cycle—commission, operate, vent, recommission—ensures that system functionality remains predictable and safe as ITER moves towards full fusion performance.

The philosophy behind ITER’s commissioning strategy is to build capability step by step. “The goal is to arrive at the end with a tokamak and a plant that are ready for plasma operation,” says Nunes. “Everything must already work the moment we start plasma commissioning.”

*Several of ITER’s toroidal field magnets and one poloidal field magnet will be cooled down and tested in the on-site magnet cold test facility. The central solenoid magnets were also cold tested at their operating temperature of 4 K.