Join the Club!

1 Oct 2012

-

Robert Arnoux

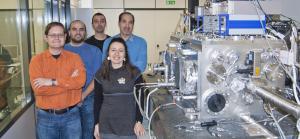

David Jezeršek (left, with his colleagues at the Elettra Synchrotron in Trieste, Italy) created the Unofficial ITER Fan Club website at age 27 in September, 2005—about a year before Newsline published its first issue.

Seven years ago, about a year before Newsline published its first issue, a 27-year old student at the Jožef Stefan Institute (JSI) in Ljubljana, Slovenia, sat frustrated in front of his computer. Googling the word "ITER," this "mind-blowing" project some of his colleagues were in contact with, didn't return much relevant information. For internet-savvy David Jezeršek, this was an injustice to be repaired.

"Here we had this fantastic project aiming at artificially recreating physical reactions similar to those occurring in the Sun and stars," he remembers fuming, "and there was almost nothing on the Web to help people understand what it was all about..." The creation, in September 2005, of the Unofficial ITER Fan Club website was David's answer to this paradox.

"The idea," he explains, "was to collect the meagre ITER-related news that was published here and there in news portals and websites. I didn't have grand ambitions, I just thought this would be a way to keep in touch with the project, monitor its progress and share that information with whoever connected to the site."

The Unofficial ITER Fan Club website soon developed into a patchwork of news, announcements, quotes and book reviews. Membership rose steadily until—a victim of its own success!—spamming and "some automatic scripts that create accounts without human intervention" forced David to close the registration process.

The 430 "confirmed members" (65 students, 81 engineers, one actor, two historians, etc.) who are listed on the site's front page are the original fans and their number does not reflect the actual traffic generated by the site. As this article was being written, more than 20 people were connected and, according to Google Analytics, the Unofficial ITER Fan Club website has been visited by more than 100,000 people since October 2006, 22 percent of them coming from the US; 17 percent from Germany; and 10 percent from the UK. "Quite surprisingly," says David, "France ranks only 4th, with 7 percent of the total visits."

As a revamped ITER official website was launched in May 2009, traffic to its unofficial counterpart inevitably declined. For David, it was both "unfortunate" and inevitable. The lone, enthusiastic student had done his part; now the official institution was taking over. "Iter.org became more and more informative," he recalls, "which was a very good thing for the project."

As for the present, David acknowledges that, considering the amount and quality of the information Iter.org provides, "the need for a separate, unofficial ITER website has diminished." This does not mean, however, that his creation is obsolete. "The site could be a good base for community building—a forum where ITER enthusiasts would meet and discuss."

Seven years ago, when he created the Unofficial ITER Fan Club website, David was a graduate student preparing a diploma in physics and later material science, which left him a reasonable amount of spare time. Now, as a post-doc at the Elettra Synchrotron in Trieste, Italy, the situation is different: "I can't find time to administer the website properly. I need a forum administrator—I hope that a web-literate fusion enthusiast reading this interview will contact me for the job ..."

Whatever the future holds for the Unofficial ITER Fan Club and its website, David's creation will remain as a testimony of a time, pre-dating the establishment of the ITER Organization, when communicating the ITER Project relied almost exclusively on enthusiasm, goodwill and personal initiative.