Lessons learned from SPIDER, a full-size negative ion source

SPIDER finished its first test campaign in late November 2021 and is now entering an upgrade phase. During this time, the testbed will be shut down for about one year to make changes based on what was learned during the campaign.

SPIDER is one of two separate testbeds that will ultimately be installed at the facility. The second, called MITICA, will be a full prototype of a heating neutral beam injector on the same scale as the injectors that will heat the plasma at ITER.

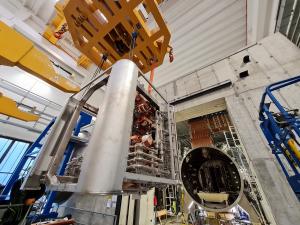

The core of both test beds is the ion source, where the negative ions are generated in an ionized gas (plasma) and extracted from the plasma in the form of thousands of individual beamlets by means of multi-aperture electrodes (dubbed "grids"). The ion source is almost the same for both experiments, but MITICA will have an additional five grids to accelerate beams to 1 MeV—ten times the energy of SPIDER.

While SPIDER lacks the power density of MITICA, it is still a full-size negative ion source that makes it possible to study the production of high-current negative ion beams before assembly of the high voltage equipment that will be used in MITICA and to anticipate part of the experimental program. MITICA, in fact, is not expected to start experiments until late 2024.

"Our job is to observe what happens at the Neutral Beam Test Facility to learn things that can be used to improve the design of the neutral beam systems for ITER," explains Pierluigi Veltri, Neutral Beam Coordination Officer. "We have already done this for some sub-systems. For example, during testing, imperfections were discovered in a magnetic field activated within the ion source. To fix the problem, the position of some conductors was changed to optimize the magnetic field topology. We immediately took this new design and implemented it in the diagnostic neutral beam ion source, which like SPIDER, operates at 100 kV and which will be used to diagnose the properties of the ITER plasma."

New discoveries

"We started testing SPIDER in 2018," says Veltri. "In the beginning the idea was to operate for one year and then do upgrades. But then we extended the campaign to three years."

Because SPIDER is both the largest negative ion source in the world and the only one running in a large vacuum, testing often yields discoveries that require changes. One example of this is that after a few months of testing it became clear that an enhanced vacuum system would be needed. The long procurement time of the new vacuum system was one of the reasons the campaign was prolonged.

It the meantime, the team implemented a workaround that led to some surprising observations. The experiments were modified so that instead of opening all 1,280 apertures (each about 1.5 cm in diameter) on the first grid, some were covered up. As a result, individual beamlets passed through only some of the holes.

"When you open all the apertures, you can't tell any of the beamlets apart," explains James Zacks, Neutral Beam Test Facility Scientist. "But the separate beamlets allowed us to see how tightly, or broadly, the beams diverge. We are now trying to understand how to get the beams as narrow as possible so we can avoid heating the sides of the beam line, which is a waste of power. We want to concentrate that power as much as possible."

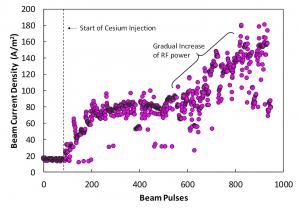

Another major achievement occurred relatively late in the testing campaign when cesium operation was tested in May 2021. Cesium is used as a catalyst to get negative ions out of hydrogen using a technique that has been known for years but never tested on a large-scale ion source.

"We demonstrated that cesium injection was effective, even with reduced source power," says Veltri. "We went from an extracted current density of 20 to 30 amperes per square metre all the way up to 170 amperes per square metre."

Changes and upgrades

"One of the big changes we're making is to replace the old-style radio frequency tetrode oscillators with solid state amplifiers," adds Zacks. "Ion sources are powered by a radio frequency power supply. When MITICA was being designed, tetrode oscillators were the standard but now there are better options. We have more confidence in solid state, which will allow us to resolve some of the issues associated with the tetrodes."

"The new solid state power supply will make it possible to achieve the full power of the ion source, which is 800 kW," adds Veltri. "Until now we could only operate at half that power."

"The additional time has also allowed us to improve some of the diagnostics on SPIDER," says Zacks. "Because the heating neutral beams will be run in a tokamak, we will be very limited in what we can do with diagnostics at ITER. However, SPIDER is not constrained by a nuclear environment and complex physical access. That gives us the opportunity to add the diagnostics to the testbed to better understand the physics."

The upgrades that will be installed within the next year are expected to allow testing at full intensity and for the required duration—1000 seconds for hydrogen, and one hour for deuterium.

"We learned a few things and are now making several big upgrades," explains Zacks. "That's how engineering often works."