The "doughnut method" and the Perhapstron

Fifty years ago, in its February 3,1958 issue, the Life Magazine published a cover story on Shirley Temple launching a new TV series. Also in this issue was a long article on the Russian Revolution, another one on Americans on the move, countless (almost forgotten) ads for cigarettes - and a double page on fusion energy.

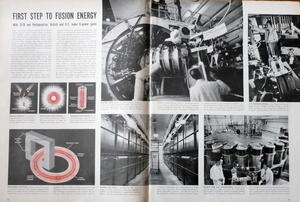

For the story, not only the Harwell Laboratories opened their doors, where the British had been operating the famous Zeta machine (Zero Energy Thermonuclear Assembly) since 1954. They were also allowed to Los Alamos to get a glimpse of the Perhapstron — a so called "pinch" machine, that magnetically squeezes the plasma to a point where fusion reactions would occur.

It was the first time an article on fusion research appeared in a general audience magazine and there was good reason for it : A week before, a "restrainedly jubilant announcement" had been issued by Harwell and Los Alamos laboratories announcing to the world that a plasma temperature "up to 5 million degrees" had been attained in both machines and "with them, scientists cautiously believe(d), brief fusion".

The article described the fundamentals of fusion physics, its perspective and challenges: harnessing fusion, "the same energy that keeps the sun's fires burning", would provide "unlimited power from an inexhaustible source". But "final control of this energy might still be a lifetime away". In 1958, the word "tokamak" was yet unknown to scientists and reporters in the Western world. If fusion was to be achieved, it would be by way of the "doughnut method"...

Fifty years ago, British and US fusion scientists had indeed made "H-power gains", but the "jubilant announcements", however restrained, where quite premature : the neutrons emissions which had been detected were real but, as more experiments, cross-checking and calculations were soon to demonstrate, they had nothing to do with actual fusion. The disappointment was particularly cruel for the British, who had hailed "the mighty Zeta" as "greater than Sputnik". Still, for the decade to follow, and until the Soviets unveiled the scope of their own research at the famous Novosibirsk conference in August of 1968, the Harwell machine was to prove one of most effective research installation in the already prolific field of fusion research.