Robots, tools and teams playing in unison

In an on-site building originally designed for beryllium-related activities and now dedicated to assembly preparation, as well as in factories in India and Japan, a major “project within the project” is taking shape. Its objective is to develop the robots and tooling that will enable the installation of nearly 20,000 components—large and small, and for the most part individually customized—on the inner wall of the plasma chamber. The challenge is immense: from coils, manifolds, or blanket modules attached to the vacuum vessel’s inner surface, to first-wall panels directly facing the plasma, no fewer than half a dozen “system layers,” each comprising thousands of components, are superimposed like the skins of a steel onion.

Like finely tuned instruments in a symphonic orchestra, robots, tooling and their operators will follow a detailed music sheet—an updated, streamlined work organization based on the parallelization, rather than the succession, of tasks.

“Specialized teams and assembly tools will move from one part of the vacuum vessel to the next to install a specific ‘layer’ of components. As they advance, another team moves in to install the next layer,” explains Raphaël Hery, an expert in remote handling and robotics in harsh environments like the French inertial fusion installation Laser Mégajoule and the IRIS deep-sea inspection system. Raphaël says that this strategy, which he calls the Rolling Waves concept, significantly reduces installation time and co-activity risks.

Some of the instruments that will perform the Rolling Waves in-vessel symphony already exist and will be optimized but most still need to be developed. This is where Godzilla will play a key role.

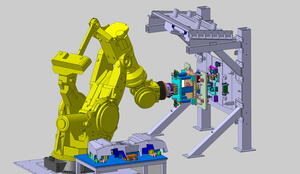

“Godzilla” is the nickname of an industrial robot—the most powerful currently available on the market—installed in the basement of the Tokamak Assembly Preparation Building. Standing an impressive 4 metres tall with an arm that extends up to 5 metres, it is capable of lifting and moving loads of up to 2.3 tonnes. Despite its mighty strength, however, Godzilla is not destined to handle in-vessel components, some of which weigh in excess of 4 tonnes. Instead, it will act as a platform for the development and integration of the tools and technologies that will be used by robots tasked with performing in-vessel assembly activities.

One of the tools being tested currently on the Godzilla platform is a partial prototype of a “tool changer,” which, as its name indicates, will enable assembly robots to quickly and safely switch from one tool to another in accordance with work sequences. As more than 30 types of specific tools will be necessary during in-vessel assembly (for handling, bolting, welding, inspecting, cutting…), this capability is a critical time-saver.

Industrial “off the shelf” robots have brains, arms, joints and muscles but they lack two essential human abilities—the sense of sight and the sense of touch. The bespoke robots that will operate inside the ITER vacuum vessel will have both. Equipped with a vision system initially developed by the European Domestic Agency, Fusion for Energy, they will be capable of precisely aligning each tool with the vacuum vessel installation targets. As for the sense of touch, it will be provided by a “force and torque sensor” that will allow the robots inside the ITER vacuum vessel to “feel” and control the movements, pressure and forces exerted on a component or an attachment interface.

“In the restricted and densely packed environment the assembly robots will be operating in, the sense of sight and touch will be essential to ensuring precise and secure movement that does not damage the vacuum vessel or nearby components,” says Raphaël. Beginning in March, Godzilla will test the tools under development on mockups and interfaces representative of the in-vessel environment.

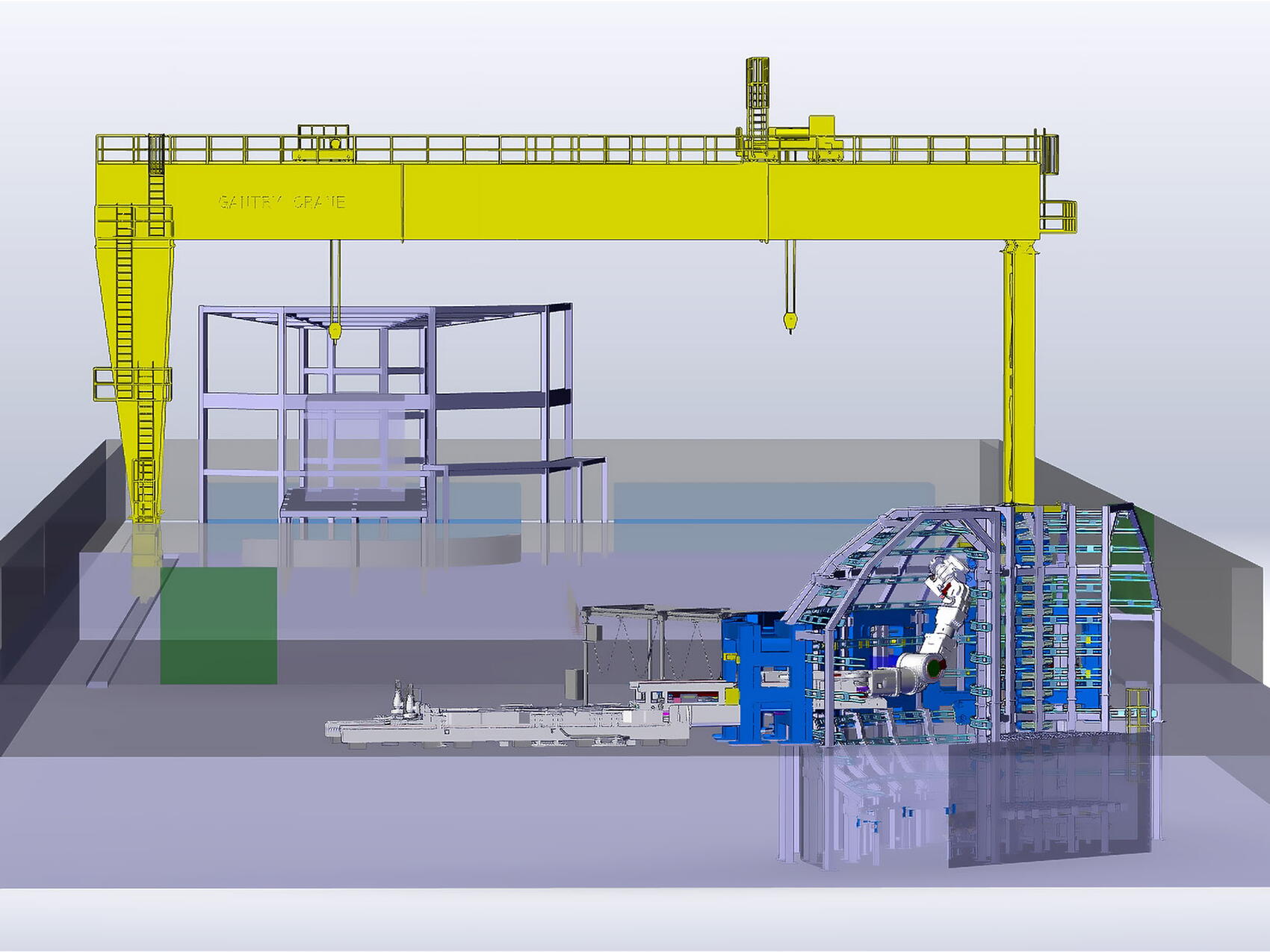

Once validated on the Godzilla platform, the tools and technologies whether developed in-house or by the Japanese Domestic Agency, will be transferred and integrated into the robots that are designed to carry out the in-vessel assembly tasks—one, the in-vessel tower crane, originally produced and delivered by CNIM, will be adapted and optimized; the other, the blanket assembly transporter, a 36-tonne monster three times the size of Godzilla, is currently in the detailed design phase prior to fabrication by Larsen & Toubro Ltd in India.

In the current Rolling Wave approach, two heavy-duty blanket assembly transporters and one in-vessel tower crane (with a second as backup) will operate in parallel, while operators on bespoke mobile elevation work platforms, equipped with “zero gravity arms” also under development, will perform manual operations.

Preparing the in-vessel assembly phase, however, covers a broader scope than what is presently happening in the Tokamak Assembly Preparation Building, at Larsen & Toubro Ltd in India, at the Naka Institute for Fusion Technology in Japan, or in other Domestic Agencies (Europe, for example, is procuring the in-vessel divertor remote handling system).

On site, two 1:1 “bare-bones” steel structures—each representing one-third of the ITER vacuum vessel (see illustration)—will allow operators to practice their skills with the actual assembly robots. One, located inside the former Cryostat Workshop, will accommodate an in-vessel tower crane; in an adjacent building, currently under construction, a similar installation will host a blanket assembly transporter and other heavy equipment dedicated to the ferrying, handling and installation of blanket modules. In anticipation of still more works to come, space is being reserved in other buildings on the ITER platform.

“Developing robust systems and processes to prepare for in-vessel assembly is a truly colossal task,” says Raphaël. “And although actual operations are still years away, the teams are under a very tight schedule.” When everything is set up and ready, the Rolling Wave symphony will be performed—almost without intermission—24 hours a day, 6 days a week for an anticipated two years.