Cooling water system

The tanks within a tank

11 Jan 2021

Deep inside the bowels of the Tokamak Building, the entrance to one of most spectacular rooms of the whole installation resembles that of a broom cupboard. The staircase is temporary and the wooden door at the top barely wide enough to allow passage.

Lying on the floor at the edge of the tank's skirt, a specialist from Italian contractor Cestaro Rossi is welding the final anchorage system (anchor bolts, shear pins and seal lids) to the steel plates deeply embedded in the concrete floor.

We once described the vast space it opens into as a "many-mirrored room." At the time (in January 2018), workers were busy lining the floor and the lower walls with stainless steel panels. The view was striking: an immense volume, empty, and large enough to contain a three-storey building (40 metres long, 15 metres wide, and 11 metres high).

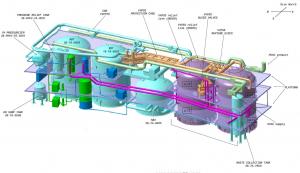

The room was being prepared to accommodate a set of massive water storage containers: three drain tanks to support normal operation, maintenance and water collection following an accident in the machine; and four vapour suppression tanks, stacked two by two, to protect the vacuum vessel against overpressure in case of a "loss of coolant accident" in the vacuum chamber. Containing contaminated water, the tanks act as a first confinement barrier and form one of the key safety systems for the ITER machine.

What was once a vast and shiny expanse has turned into an overcrowded cavern. Sheets of protective plywood cover the stainless steel lining of the floor and lower walls; light is scarce and focused on working areas.

The room itself was designed as a tank, ensuring that, in the event of a leak, contaminated water would remain contained within, its steel lining acting as a "drip pan" just like the tray that collects drippings from roasting meat.

In August 2018, in one of the most spectacular activities yet performed in the Tokamak Complex, the tanks were positioned inside the room and anchored with temporary bolts pending the development of a design for an anchorage system compliant with the tight safety requirements (leak tightness, resistance to seismic events) of the system.

By the end of 2019, the design, drawings and calculations were finalized and work began on the final installation—a particularly challenging operation considering the size and weight of the tanks and the very constricted space left for operators.

As the room itself acts as a "secondary tank," the leak-tightness of the welds is paramount. Here, the multi-pass welding of a shear pin designed to withstand lateral accelerations in the case of a seismic event.

One year later, what was once a vast and shiny expanse has turned into an overcrowded cavern. Sheets of protective plywood cover the stainless steel lining of the floor and lower walls; light is scarce and focused on working areas.

In order to install and weld the final anchorage system, the tanks—more than 6 metres tall and weighing up to 180 tonnes— have been lifted some 30 centimetres by way of hydraulic jacks. In this position, standing very close together, the tanks nearly reach the concrete roof two levels above.

Welded on the embedded plates, the anchorage system (bolts, seal lids and shear pins for withstanding lateral seismic accelerations) must be absolutely leak-tight. Non-destructive tests are performed on each individual weld, including a leak tightness performed using a vacuum box specifically designed and customized to fit the geometry under the skirts of the tanks. There are 280 welds, amounting to a total weld length in excess of 400 metres.

Three drain tanks to support operation in normal and incidental situations; four vapour suppression tanks, stacked by twos, to protect the vacuum vessel in case of a "loss of coolant accident" in the vacuum chamber. The large volume of the tanks makes for a very congested environment in the drain tank room.

The welding and testing of the anchorage system for the entire set of tanks was completed on 16 December 2020; however, a lot of work remains to be done. This month, the tanks will be lifted again to allow the steel liner under the skirts to be cleaned and "passivated" (a chemical process that prevents corrosion). Also, the piping needed for First Plasma must be installed and platforms erected to allow access to all parts of the tanks and to the support equipment such as valves, heat exchangers and pumps.

Sometime in the near future, with the steel lining shining, the dark cavern will regain something of the splendour of the "many-mirrored room" ... albeit a very crowded one.