George H. "Hutch" Neilson heads the Advanced Projects Department at the U.S. Department of Energy's (DOE) Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory (PPPL), where his responsibilities include advanced design and planning for future fusion initiatives. Neilson manages collaborations with stellarator projects in Germany and Japan, and is the US leader in developing collaborations with South Korea and China on the design of next-step fusion nuclear facilities.

During the past year, Neilson has played a leading role in promoting international collaboration on the development of fusion technology programs directed toward a magnetic fusion DEMO, and he has been instrumental in launching a new DEMO program workshop series under the auspices of the International Atomic Energy Agency.

At PPPL, which he joined in 1989, he has led national physics design activities for a series of fusion experiment projects, including the Korea Superconducting Tokamak Advanced Research (KSTAR) and PPPL's National Compact Stellarator Experiment (NCSX) project, which he oversaw from its inception in 1998 through fabrication of its major components.

A MIT graduate, Neilson is a fifty-year fusion veteran who joined Oak Ridge National Laboratory in 1974.

Newsline: Worldwide conferences on fusion are many. What is SOFE's specificity?

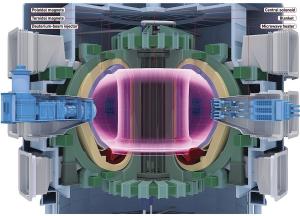

Hutch Neilson: SOFE's focus is fusion engineering. Fusion engineers have the crucial task of producing the components and systems needed to advance fusion physics and technology. Progress toward fusion energy systems, both magnetic and inertial, can be measured by the advances in the degree of system integration in fusion research facilities. Today's fusion engineers confront the challenges of large, industrial-scale facilities such as the National Ignition Facility (NIF) and ITER. They use advanced technology to obtain self-consistent solutions to demanding physics requirements, integrating large numbers of components on an unprecedented scale. SOFE attracts leaders from the international fusion research community, providing a venue for a multilateral exchange of information among physicists, technologists, and engineers. The first symposium, held in 1965 in Livermore, California, was called "Symposium on Engineering Problems of Controlled Thermonuclear Research." Years ago the name was simplified to "Symposium on Fusion Engineering" and today the series coverage has expanded to include such topics as project management and system integration. But, the focus is still very much on fusion's challenging engineering problems and their solutions.

What will be the highlights of this year's 25th edition?

The completion of NIF and ITER's transition from design to construction mark a transition to a new phase of the world fusion enterprise, in which the focus is increasingly on the final steps to fusion's energy goals. SOFE-2013 will advance the international technical discussion concerning the engineering of current projects including NIF and ITER, but also of next-step programs and facilities on the roadmap to the realization of fusion. Participants will have the opportunity to tour the National Ignition Facility. The symposium will feature plenary talks from China, South Korea, and the European Union, discussing ambitious plans, including new fusion nuclear facilities, aimed at fusion electricity generation by mid-century. ITER will be prominently featured in several of the fifty or so invited papers, as well as in plenary talks by the 2011 Fusion Technology awardee and ITER Deputy Director-General Remmelt Haange and by Deputy Director-General Carlos Alejaldre. Invited papers from several operating tokamaks and stellarators will emphasize their accomplishments and plans in support of fusion next steps.

The 2011 SOFE, in Chicago, called for "bolder steps forward" in the realization of commercial fusion energy. In your opinion, have these steps been taken?

Yes, much has happened in this regard since SOFE-2011. For a few examples, the European Fusion Development Agreement has rolled out a roadmap calling for a demonstration fusion power plant to start operation in the early 2040s with the goal of demonstrating net electricity by 2050. China and South Korea are both studying design options for next-step fusion nuclear devices, and are making plans to start construction in the 2020s. And, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) has launched an annual DEMO Programme Workshop series to foster international collaboration and broaden the international technical discussion on DEMO technical issues. The first of these workshops was held at UCLA in October 2012.