The story behind the coffee mug

At ITER, it’s common to see whiteboards covered with physics equations. What’s less ordinary in the offices, although increasingly prevalent, is a dark blue coffee mug with one of these equations handwritten along its side. It is not the formula most closely associated with fusion—the one that describes the deuterium-tritium reaction. So what’s the story behind it?

The rather elegant formulation, aesthetically pleasing even to the unscientific eye, is known as the Grad–Shafranov equation. In the very simplest terms, it is the equation that allows scientists such as Yuri Gribov at ITER to set the right conditions for keeping the position of the burning plasma stable and keeping the gap between the plasma and the walls of the tokamak chamber sufficiently far apart.

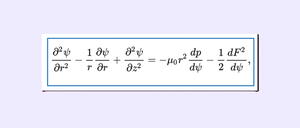

In rather more detail, Grad–Shafranov is a mathematical equation that describes the balance between magnetic forces and plasma pressure in an axisymmetric plasma like those in tokamaks—the “equilibrium equation in ideal magnetohydrodynamics (MHD) for a two-dimensional plasma” (read more here).

It is fitting that the equation on the ITER mug is in Gribov’s handwriting, as there is a direct connection between him and Vitaly Shafranov. After graduating from Moscow State University in 1977 Yuri joined the Kurchatov Institute, first working under the supervision of Valery Chuyanov, who went on to lead the Fusion Science and Technology Department at ITER from 2006 to 2012, and later joining the Theoretical Department headed by Vitaly Shafranov.

“The Grad–Shafranov equation is the foundation for modelling the magnetic control of tokamak plasma,” Gribov explains. “Derived from fundamental physical principles, it has been repeatedly verified through experiments, and this is precisely what makes our calculations of the plasma’s position and shape in the tokamak so reliable.”

Gribov remembers Shafranov as a sensitive, gentle, and highly intelligent man—a “genius.” “For so much of his early career, his work in fusion was kept secret. When the secrecy classification was lifted, it began to be published in scientific journals. Later in life, he was very highly regarded as a teacher and mentor, and students loved to work with him. He prepared many, many students for their PhDs, and many went on to establish careers for themselves—such as Leonid Zhakharov, at Princeton, and Vladimir Pustovitov, at the Kurchatov.”

So where does the ‘Grad’ part of the equation come from?

“The equation bears both names because Grad and Shafranov derived it independently, and almost simultaneously, but using different approaches,” explains Gribov.

Harold Grad was an American applied mathematician, working on the general theory of plasma equilibrium in magnetic fields using MHD equations. His approach used a variational principle: finding a magnetic flux function that minimizes the system’s energy for fixed pressure and current¹.

Shafranov for his part was focused on practical plasma confinement in a torus explicitly accounting for toroidal geometry in which the magnetic field is non-uniform and varies along the radius and height of the torus (as in a tokamak). He derived the equation for the force balance in a toroidal magnetic field².

Shafranov’s results turned out to be mathematically equivalent to Grad’s more general formulation, but with a direct focus on toroidal configurations. This equation was later applied by Shafranov and Vladimir Mukhovatov to a specific tokamak configuration (with circular plasmas) for which it could be solved analytically. This provided simple formulas for key parameters for the equilibrium of a plasma in the tokamak, the so-called Shafranov shift and the Shafranov vertical field.

“Although the Grad–Shafranov equation provides a reliable model for the magnetic control of the plasma current, position, and shape,” says Gribov, “unfortunately, there are still no equally reliable models for controlling the plasma’s kinetic parameters such as the magnitude and profile across the plasma of its temperature.” The problem is the same as in accurately predicting the weather. “Like the weather, plasma has an infinite number of degrees of freedom, and its kinetic parameters nonlinearly depend on many conditions. And that’s what makes our jobs in plasma control so interesting!”

And what makes the ITER mugs so popular… (See the item here.)

¹Grad’s equation was published in 1958 in H. Grad and H. Rubin, Hydromagnetic Equilibria and Force-Free Fields, Proceedings of the Second United Nations International Conference on the Peaceful Uses of Atomic Energy, 1-13 September 1958, Geneva, P/386.

²Shafranov’s paper ‘On magnetohydrodynamic equilibrium configurations’ was published in 1957 in the Russian in Journal of Experimental and Theoretical Physics (U.S.S.R.) 33 (1957) 710-722. The paper was translated into English in 1958 in Soviet Physics JETP 6(33) (1958) 545-554.