A fast new way to see inside the vacuum vessel

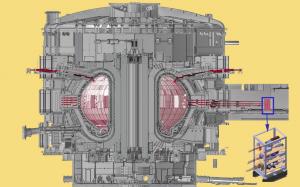

A new system, called the "in-vessel lighting system," will make it easier for ITER operators to quickly assess potential damage to the inner wall by shining visible light into the vacuum vessel and taking pictures.

Just a few centimetres away from the hot plasma in ITER is the blanket first wall, which is made of beryllium. Although designed to handle high heat flux, the wall can be locally damaged if the plasma leans on it incorrectly. Proceeding to the next pulse without first checking for issues could be costly. The plasma lean could reoccur in a subsequent pulse, leading to further damage.

Thanks to a large suite of diagnostics that measure the temperature of the wall during a pulse, operators can easily tell when something overheats. However, the sensors will not give them enough information about the extent of potential first wall damage.

When in doubt, operators can use a powerful diagnostic called the "in-vessel viewing system," which has big arms that are moved into the plasma chamber to scan the surface and measure surface topology. But that system takes a long time to deploy and run—using precious time when the reactor might otherwise be used to run experiments.

"The in-vessel viewing system is very powerful, but it isn't meant for quick and frequent checks," says Martin Kocan, Diagnostics Coordinating Scientist in the Ex-Vessel Diagnostics Section. "We need to give the operators a mechanism to look inside after any given pulse—and that could amount to many thousands of times throughout the lifetime of the project. The existing system was not designed to be deployed so many times."

A clever design uses existing equipment

As a result, the ITER diagnostics team did a conceptual design for a new system, the in-vessel lighting system, that is a little cruder, but that can be deployed quickly and often. "The new system piggybacks on an existing system, called the 'wide angle visible and infrared system,' which uses infrared cameras to take measurements of the wall temperature during a pulse. By building on top of what already exists, we've found a more cost-effective solution than if we built it from scratch," says Martin.

The wide-angle visible and infrared system takes the light from the plasma, channels it through mirrors and lenses, and sends it through 20 different optical channels to cameras. The in-vessel lighting system will add light into the chamber by sending it along the same paths, but in reverse. The light travelling through the optical fibres will come from lasers, placed far from the plasma. Each optical path will be equipped with a dedicated camera to capture images of the inside of the tokamak with high spatial resolution.

"We have 20 such views in total looking all around the tokamak routinely during a discharge so we can monitor most of the plasma-facing components," says Martin. "The in-vessel lighting system will use 19 of the 20 views to inject the light for illumination, and the remaining view to take the picture with the dedicated camera."

The new system is versatile—each view can be used to either inject light or to take an image. So at any given time, the camera from any of the views can be used.

"It still takes about 30 seconds to take each picture, because even with the 19 light sources, the illumination won't be anywhere close to the intensity you get when taking a daylight image. We will inject only about 19 W of light inside the torus. But every 30 seconds, we can change the configuration and start taking a view from a different angle."

The new system covers 80 to 90 percent of the surface area within 10 minutes

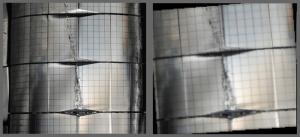

The spatial resolution of the images depends on the distance from the camera to the object, but it will be on the order of a few millimetres, which is enough to detail potential wall damage such as melt features. Some of the views overlap and software can be used to combine the overlapped images to get more detail. When the views are alternated and a picture is taken from each of the optical paths, the operation produces up to 20 full images of the torus wall.

"We expect to be able to cover about 80 to 90 percent of the vessel surface," says Martin. "That means there will still be areas we can't see at all—and of course there's a risk a melt will occur in one of those blind spots. But the views are dictated by where we can place the cameras."

The new in-vessel lighting system is fast and gives a first indication about the location and extent of any damage. It allows operators to determine within a couple of minutes whether they can safely go on with the next plasma discharge or whether the more complex system needs to be deployed to examine the first wall in more detail.

Starting from this year the team will take the conceptual design and develop it further. They are now preparing for the tender process to find a partner to do the detailed design that will ultimately be used by a manufacturer. In parallel, the team is working on securing interfaces for the system—space allocated in the ports, and provisions for electrical services and cooling water for the cameras.