John Villanueva is one of the experts of the ITER Metrology, Reverse Engineering, Inspection and Test Group. "I became involved in metrology long enough ago that I'm now one of the old-timers," he says. "I've gone from using the old-fashioned optical-mechanical scopes all the way to the laser trackers we use today. It's because I lived through those changes that I can more easily understand why we do what we do today."

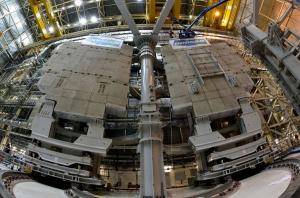

Aligning huge parts to the ITER coordinate system

All measurement tasks require a fixed reference base from which measurements can be made and calculated. As a large-scale metrology project, ITER has a three-dimensional coordinate system that consists of a collection of target "nests" and/or instrument stations that have known geometry and computed uncertainty. Inside the Tokamak Complex, the network is called the Tokamak Global Coordinate System.

"When you go into the Tokamak Building you'll see our red targets all over the building," says Villanueva. "We can use a tool to shoot any three targets, and by the magic of Pythagorean's Theorem we know precisely where the centre of our instrument is with respect to the Tokamak Global Coordinate System." The tool includes a horizontal angle encoder, a vertical angle encoder, and a laser to obtain distance. With the two angles and the distance, a triangle can be established.

"We recently had 340-tonne test loads going into one of the sector sub-assembly tools in the Assembly Hall, that had to be positioned vertical to gravity and within one millimetre," says Villanueva. "They had to be vertical to gravity for safety reasons, but also because—as part of commissioning—we had to prove that the tool could align huge parts vertical to gravity with tight accuracy."

"The sector sub-assembly tools have six degrees of freedom—and along each degree of freedom, the instruments used for metrology can measure submillimetre movements. Metrology is there, watching the component aligned onto the tool and telling the teams if it's aligned in the right position."