"Math Nobel" at extreme theoretical end of ITER

3 Sep 2010

-

Robert Arnoux

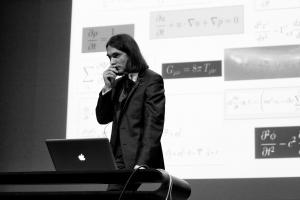

Aside from his passion for classical music and spiders, there is nothing this flamboyant young man loves more than equations. © CNRS

There is actually no Nobel Prize in mathematics. There is, however, an international award which is universally recognized as its equivalent: the Fields Medal, which is awarded every four years by the International Mathematics Union (IMU).

The most prestigious prize a mathematician can receive, the Fields Medal gives recognition and encouragement to younger (under 40) scientists who have made a major contribution to their field of research.

On 19 August in Hyderabad, India, where the IMU had convened, French mathematician Cédric Villani, 37, was one of four 2010 Fields Medal laureates—two Frenchmen, one Israeli and one Russian.

A full professor at the elite Ecole Normale Supérieure in Lyon and the director of the Paris Institut Henri Poincaré, Villani has been praised for "providing a deep mathematical understanding of a variety of physical phenomena."

Aside from his passion for classical music and spiders, which explain his romantic poet look and the large spider brooch he wears, there is nothing this flamboyant young man loves more than equations.

One of his favourites is the Vlasov equation: a three-line long list of numbers and symbols that can describe, among other things, the behaviour of particles in a plasma or the movements of stars in a galaxy.

"I work at the extreme theoretical end of ITER," said Villani in a recent interview for French daily Le Figaro. To Newsline, he explains: "I am not directly involved in the project, but in trying to get a better understanding of the equation's properties I can bring a contribution ... a modest one, certainly, but every contribution is valuable. I strongly believe in ITER and that interview in a national daily was an opportunity for me to advertise the project ..."

Villani's theoretical work will help those working in "numerical analysis" to develop algorithms, which, in turn will be used to optimize computational models of plasma behaviour.

Over the past decades, many prominent mathematicians have pointed out that a sharp mathematical understanding of equations governing physical phenomena is a key to the design of accurate numerical recipes.

A theoretician who may appear to the layman as lost in abstraction, Villani feels it is "important to be anchored in reality." Reality meaning, in his case, the frenzied agitation of particles in a plasma and the majestic motion of stars in faraway galaxies.