The visitors' room at the National Fusion Research Institute (NFRI) in Daejeon, Korea offers one of the most dramatic illustrations of the progress accomplished by fusion research and technology over the past 30 years.

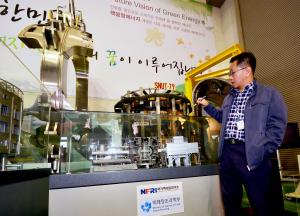

Standing behind mock-ups of ITER and KSTAR, a small, partially rusted device attracts attention. The device looks old although it isn't really: the Seoul National University Tokamak (SNUT-79) operated between 1982 and 1992.

The contrast between SNUT-79, Korea's first significant step into fusion research, and KSTAR, the large superconducting tokamak that entered operation in 2008, is striking. Although the two machines are only twenty years apart they seem to belong to totally different worlds—as if the Wright brothers' Flyer was parked next to an Airbus A380.

It is a small walk from the visitor's room to the large hall that houses the KSTAR tokamak. The machine, more than 10 metres in diameter, is impressive, remarkably squat and compact. Having just completed its 2012 campaign, it now stands idle. "The machine is undergoing an important overhaul," explains Hyung-Lyeol Yang, the Tokamak Engineering Division head at the KSTAR Research Center. "Several key hardware components are being modified and upgraded in preparation for the next campaign."