3,000 sensors for detecting the quench

A robust detection system is under development to protect the ITER magnets in case of quenches—those events in a magnet's lifetime when superconductivity is lost and the conductors return to a resistive state.

Magnet quenches aren't expected often during the lifetime of ITER, but it is necessary to plan for them. "Quenches aren't an accident, failure or defect—they are part of the life of a superconducting magnet and the latter must be designed to withstand them," says Felix Rodriguez-Mateos, the quench detection responsible engineer in the Magnet Division. "It is our job to equip ITER with a detection system so that when a quench occurs we react rapidly to protect the integrity of the coils."

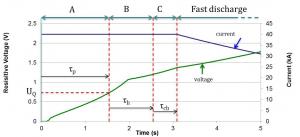

The primary detection system—called the investment protection quench detection system—will monitor the resistive voltage of the superconducting coils (there is also a secondary detection system, see box below). Why the voltage? "Whereas during superconducting operation the resistive voltage in a coil is practically zero, a quench would cause it to begin to climb," explains Felix. "By comparing voltage drops at two symmetric windings for instance, the instruments will detect variations of only fractions of a volt."

"The tokamak environment will be a very noisy one for our instruments—that's one of the challenges of quench detection in ITER," says Felix. "The difficulty will be to cull out false triggers while at the same time not allowing a real quench to go undetected," says Felix. "We have tried to build enough redundancy into the system so as to minimize false signals. We don't want to discharge the coils and lose machine availability if we don't have to."

In addition, an R&D collaboration has been underway at the superconducting Korean tokamak KSTAR since 2009 to learn more about compensating the electromagnetic fields. ITER is collaborating with the KSTAR magnet team to gather information on the electromagnetic signals picked up by the superconducting cables during plasma disruptions. This data will assist the ITER team in designing compensation systems to separate the electromagnetic noise of a disruption from a quench.

"Quench detection in ITER is the most challenging around," concludes Felix, who has approximately 25 years of experience in the field. "At the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), for instance, we were working with faster detection times. But in ITER, there will be a tremendous amount of interference for the instruments to sort through—electromagnetic noise, swinging voltages, couplings, perturbations. At ITER, we are also dealing with higher current, bigger common mode voltages, and larger stored energy. We'll be pushing quench detection and protection to the limit of technology today."