Huffing and puffing

Testing the endurance of steering mirror bellows

19 Nov 2018

-

Kirsten Haupt

On the computer screen, a set of three metal bellows "breathe" in a steady rhythm. Nuclear engineer Natalia Casal and materials engineer Toshimichi Omori are on a Skype call with the Swiss Plasma Center in Lausanne to witness a specially designed endurance test for this equipment, which is critical to the rotation of steering mirrors that will direct high-frequency microwave beams into the ITER plasma.

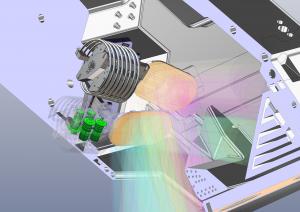

This is a simulated view from the plasma centre looking up into the upper launcher along the microwave beam path. The outer launcher structure is removed so that the steering mirrors—in orange—are visible. The mechanism of the top steering mirror is intact; the mechanism of the lower mirror is "dematerialized" so that the four bellows—in green—can be seen.

Thousands of times during the operational lifetime of ITER, the steering mirrors of the electron cyclotron heating system will pivot to direct powerful microwave beams to the appropriate location in the plasma.

The steering mirrors are part of the electron cyclotron upper launchers, the delivery mechanisms that will "launch" 24 microwave beams generated by the electron cyclotron heating system into the vacuum vessel during full operation. The main functions are to provide central heating and current drive to the plasma, and to direct heat to localized areas within the plasma to prevent instabilities from cooling it down.

In addition, operators will rely on the electron cyclotron system to deliver the "spark" that initiates each plasma. Inside of the upper launchers, two steering mirrors direct the beams into the plasma where they target a set of fixed mirrors on the central column with millimetre precision. From there the beams spread out and pan across the "plasma null," the optimum region for initiating the plasma.

Natalia Casal during a Skype video conference reviewing the launch of the bellows test stand at the Swiss Plasma Center.

About 30 cm wide and 15 cm high, the steering mirrors consist of two parts: a stainless steel body and a reflective top layer made of a copper-chrome-zirconium alloy. The biggest challenge, however, is the mechanism that powers the mirrors' precise rotational capabilities.

Conventional steering mechanisms use traditional ball bearings controlled by push-pull rods to allow mirror rotation, but in the harsh environment near the ITER plasma these would tend to jam. In addition, this mechanical solution would require lubricant to prevent friction, which could potentially contaminate the vacuum environment. "Similar to the ultra-high vacuum instruments that were developed for use on board the International Space Station, we had to come up with an innovative solution," says Casal.

To avoid this problem, engineers at the Swiss Plasma Center designed a frictionless system that cannot jam. Thin metallic fins replace the ball bearings and permit the necessary rotation of the steering mirrors. The fins are powered by a set of gas pistons, similar to those in a car engine, with a set of four small bellows replacing the piston chambers. About 7 cm in length and 3.2 cm in diameter, the bellows are compressed or released by helium that is pumped in and out of their casing.

The bellows are considered the weakest point of the entire steering mechanism, as they need to survive thousands of mirror movement cycles with high reliability. In collaboration between the European Domestic Agency (Fusion for Energy), the Swiss Plasma Center, the Japanese Domestic Agency and the ITER Organization, engineers in Lausanne are currently conducting a first set of tests with bellows manufactured by the Japanese company Kuze.

This endurance test, which runs for several months, involves a test rig to compress and extend the bellows over millions of cycles in order to demonstrate their compliance with the stringent ITER requirements.

The completion of testing is expected in early 2019 and will be followed by the final design review of the upper launcher later in the same year.

In the meantime, the bellows in Lausanne continue their huffing and puffing ...

Thank you to Natalia Casal and Electron Cyclotron Section head Mark Henderson for their contributions to this article.