ITER NEWSLINE

80

Moustiers-Sainte-Marie: A Crusader's star and royal craft

Robert Arnoux

Moustiers-Sainte-Marie: A Crusader's star and royal craft

The village of Moustiers, 50 kilometres to the north east of Cadarache, is a gateway to the Gorges du Verdon.

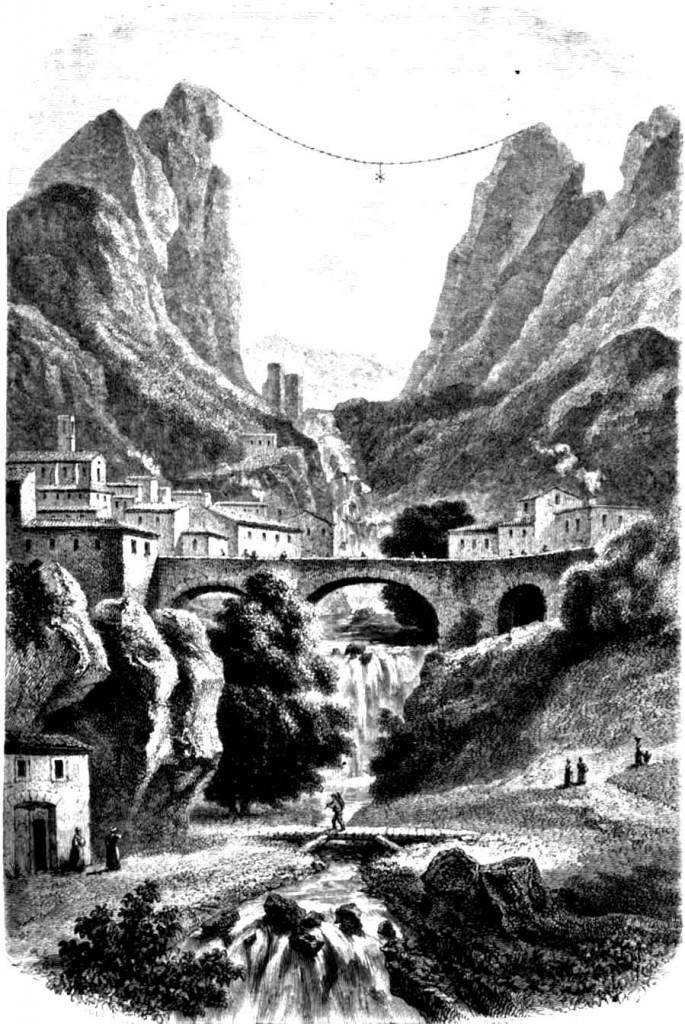

An old engraving showing the chain and star suspended by a knight returning from the Crusades.

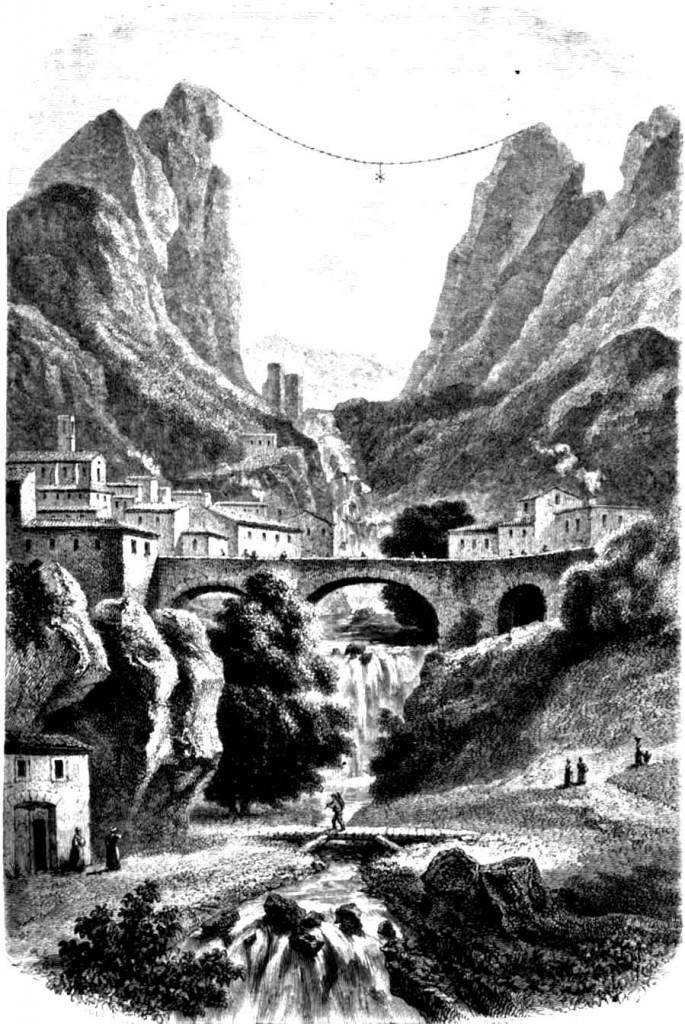

Contemporary Moustiers "faïence" with traditional 18th century cobalt blue decoration.

The first is a strange feature in the landscape. In Moustiers, a golden star hooked to a thick forged-iron chain is suspended between the two rock formations that tower over the village. Five centuries ago, scholars were already wondering who had tied this 220-metre-long necklace and for what reason. Tradition linked the peculiar adornment to a vow that a local knight had made at the time of the Crusades; should he come back safely to his village, he would dedicate a monumental iron chain and golden star to the Madonna in the Moustiers chapel. The identity of the Crusader knight may be lost, but his offering has endured more than a thousand years. Municipal services regularly make sure that the chain still holds and—once or twice a century—they replace the eroded star with a brand new one.

Some six centuries after the Crusader knight returned to Moustiers, a 28-year-old potter named Pierre Clerissy started an earthenware craft shop that was to bring worldwide fame the village. The year was 1679 and Clerissy is said to have obtained the secret of milky white enamel and fine cobalt blue decoration from a monk who came from Faenza, a small town in northern Italy—hence the name "faïence."

The wares manufactured in Moustiers during the 17th and 18th centuries were so delicate, fanciful, and of such high quality that they found their way to royal tables all over Europe. This came to an end with the French Revolution, however. With the ruin of the nobility, the Moustiers workshops closed one after another.

A revival of the "Faïence de Moustiers" occurred in the late 1920s, with the establishment of a museum and, some years later, the creation of new workshops. There are presently approximately a dozen of them; catering to tourists rather than to royals this time.

return to Newsline #80