On 18 April 1956 a Soviet warship, escorted by two destroyers, pulled up to the dock in Portsmouth, UK. On board were two of the most powerful and enigmatic men of that time: Nikolai Bulganin, President of the Council of Ministers of the USSR, and Nikita Khrushchev, Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party. The invitation had been extended by Prime Minister Anthony Eden at a Summit meeting held in Geneva the year before. Three years after Stalin's death, the time seemed ripe for an easing of tensions between the two "blocks" and for a shift toward "the peaceful coexistence between states with differing political and social systems," to use Khrushchev's words to the Twentieth Congress of the Communist Party (February 1956).

The arrival of the cruiser

Ordzhonikidze caused a sensation. It was the first-ever state visit of Soviet leaders to the West.

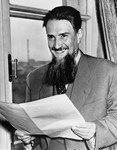

If Bulganin and Khrushchev were the focus of the crowds and the media at first, a third man was about to emerge from the shadows and steal the show: Igor Kurchatov. In charge of the Soviet nuclear program since 1943, he had achieved the construction of an atomic bomb in 1949 and a hydrogen bomb three years later, effectively giving the Soviet Union strategic equilibrium with the US—the sine qua non condition for "peaceful coexistence" with the West.

With the USSR on equal footing with the US, "The Beard," as he was known to colleagues, had been able to turn his remarkable energy to another quest, maybe the most promising but also the most difficult of all: "the thermonuclear synthesis problem" — in other words, the harnessing of thermonuclear energy for peaceful uses.

And with the blessing of his political patrons "The Beard" was ready to share his results, doubts, and expectations with scientific peers from the West.

Why the sudden transparency? Neither history, nor archives nor published memoirs furnish a satisfactory answer. It is probable that Kurchatov was convinced that the resources of one nation alone would never be enough to solve the fusion challenge. There is some indication also that he was pleased to be able to show his hosts that—on a scientific and technological level—his country was at least as advanced as theirs.

Whatever the motivation it is hard to imagine, from a distance of 60 years, the impact and echo of Igor Kurchatov's conference at the Atomic Energy Research Establishment in Harwell, Oxfordshire — the Holy of Holies of Britain's nuclear research.

Soberly titled "The possibility of producing thermonuclear reactions in a gaseous discharge," his

address was a watershed moment in the young history of fusion research.

But not because it contained any revelation. The 300 Harwell physicists who attended the conference discovered that Soviet scientists "had been following very similar lines of research into magnetic confinement as the UK and the US," write Gary McCracken and Peter Stott in

Fusion: The Energy of the Universe.

Like their American and European counterparts, the Soviets had developed straight and toroidal pinch experiments, observed neutron emissions and short spurts of hard X-rays in deuterium plasmas, and acknowledged that quite a number of facts "remained to be explained."

Backed by equations, diagrams and high-speed photographs of plasma discharges, Kurchatov's speech did not contain an explicit call for international collaboration. But in shedding light on methodology and experimental results it challenged scientists in the West to reciprocate.

While scientists on both sides were eager to collaborate, many in Western government circles were reticent, especially in the US where it was felt that the Soviet opening was a ruse—a trick to lure politically naïve physicists into giving away precious state secrets.

It took time to convince politicians that, at that stage, collaboration in the field of fusion was aboutfundamental science and didn't pose any threat of a strategic or military nature. Only in September 1958, in Geneva where the United Nations held its Second International Conference on the Peaceful Uses of Atomic Energy ("Atoms for Peace"), did the seeds that were sowed in Harwell begin to sprout.

There, for the first time and with the blessing of their governments, the main actors on both sides of the Great Divide—Artsimovitch, Teller, Spitzer, etc.—met face-to-face and exchanged notes. "They had a tremendous amount in common," writes Robin Herman in in

Fusion, The Search for Endless Energy—"an idealistic goal, a daunting intellectual problem and [...] a parallel history of frustration."

A "world fusion community" was born, determined to embrace what Kurchatov's speech had described as "the extraordinarily interesting and very difficult task of controlling thermonuclear reactions."

Sixty years after Harwell, the task — considerably longer and more difficult than anticipated — is nearing completion.

http://www.iter.org/mag/9/64-R.A.